The 19th Regiment US Colored Troops from Queen Anne’s County

The Kennard African American Cultural Heritage Center (KAACHC) in Centreville, dedicated in 2019 in the old 1936 Kennard High School, is the premier source of Queen Anne’s County Black history. In addition to hosting various programming, classes, and events, the Center is home to the African American History Museum, which features stories of local Black veterans. This past April, KAACHC installed a plaque outside the entrance honoring Civil War veterans. The memorial reads in part, Without the military help of black freed men, the war against the south could not have been won. – President Abraham Lincoln.

At the start of the Civil War in April 1861, efforts of Black men to join the military were rejected. This changed after January 1, 1863, when President Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation declaring freedom for all persons enslaved in Confederate states. The proclamation, along with the need for more Union soldiers two years into the war, fueled the recruitment of Black men, something further ignited by none other than Eastern Shore-born Frederick Douglass in his fiery campaign urging Black men to enlist.

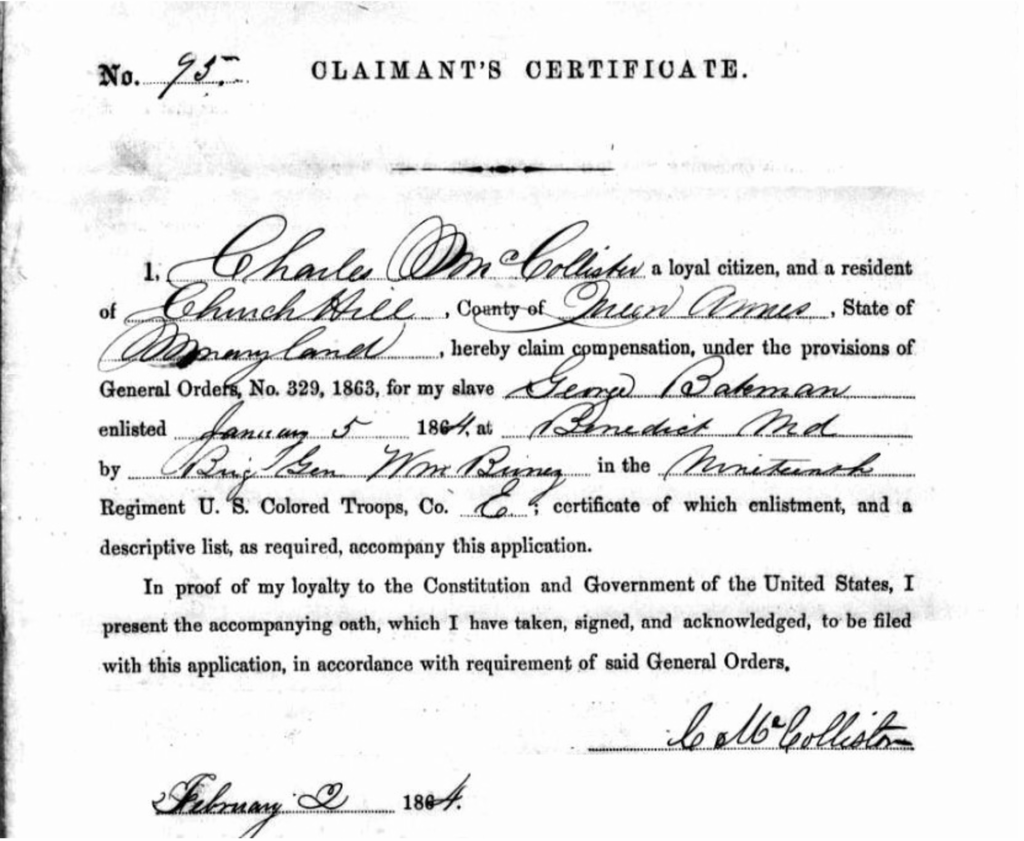

But slavery remained legal in Maryland until November 1, 1864; therefore, from late 1863 until late 1864, the state recruited Black men in part by offering enlistment bounties of $100 to $300 to enslavers, many of whom recognized that slavery would likely end, anyway.

The certificate of Charles McCollister of Church Hill claiming compensation for George Bateman, who enlisted in the 19th Regiment US Colored Troops on January 5, 1864.

Black men—freeborn, self-liberated, and freed through enlistment bounties—quickly answered the call, making up more than 200,000 United States Colored Troops (USCT) serving during the war (more than 10 percent of the Army and 25 percent of the Navy). At least 8700 of these men were from Maryland, while more than 435 came from Queen Anne’s County. Local USCT soldiers served in the 7th, 19th, and 39th regiments.

An early USCT casualty of the war was 22-year-old Benjamin Brown. Thirteen years earlier, the 1850 census listed a 9-year-old Benjamin as the son of a Kent Island sailor named Horace Brown. It should be noted that in most cases, enslaved people were counted but not named in pre-Civil War censuses; any Black person listed by name was usually not enslaved. Benjamin enlisted in the Union Army in December 1863, serving in an Eastern Shore recruiting unit. But only three months later, someone shot and killed him while he was on recruiting service in Greensboro.

Months later, the USCT 19th Regiment, initially part of the Army of the Potomac, experienced intense combat, including engagement in the Battle of the Wilderness, Cold Harbor, and the devastating Battle of the Crater, the latter of which took place during the nine-month Siege of Petersburg, VA. It was there that General Burnside planned to send in nine USCT regiments, including the 19th, to lead the charge. Although these soldiers had been specifically trained and equipped for the July 30, 1864 assault, Generals Grant and Meade vetoed the plan just one day earlier. Instead, unprepared white troops were ordered to take the lead. Mistakenly, they ran into, rather than around, the crater the army had blasted under Confederate troops. Mayhem ensued: These soldiers and those who followed found themselves trapped, open targets for Confederate gunfire from above. The Union Army suffered more than 3798 casualties, with the USCT making up more than a third of those killed, injured, taken prisoner, or declared missing.

24-year-old Sergeant James Bond, previously enslaved by Dr. James Bordley of Baltimore and Church Hill, served only seven months in the 19th Regiment before being killed at the Battle of the Crater.

Samuel Bond of the 19th USCT, not to be confused with James, is sixth from the left (front and center) in this photo of USCT soldiers, many of whom were wounded during the Battle of the Crater. Bond, formerly enslaved in Talbot County, died of dysentery in Brownsville, Texas. Infectious disease was the leading cause of death for all soldiers.

David H. Mars, an 18-year-old private from Queen Anne’s County, was initially reported to have been killed in the battle; instead, it was later learned, Confederate troops captured him and sent him to a North Carolina POW camp where he tragically died of starvation on January 30, 1865, less than three months before the war ended.

But the USCT persevered and, of course, experienced victories. The 19th Regiment USCT were among the first Union soldiers to enter and capture Richmond when the Confederate capital fell on April 3, 1865. In fact, the soldiers of both the 19th and 39th Regiments played a central role in the Appomattox campaign leading to General Lee’s April 9, 1865 surrender at Appomattox Courthouse.

Mustered in between December 1863 and late 1864 for three-year terms, 19th Regiment soldiers were not sent home when the war ended, but instead spent the following two years in Brownsville, Texas, a place prone to the dreaded yellow fever epidemics at the time. There, troops were tasked with preventing a Confederate resurgence while also maintaining peace along the border during the last two years of the “French Intervention” of Mexico.

Mustered out at Brownsville in 1867, Corporal Charles T. Hazelton returned to Queenstown. Shortly after joining the 19th Regiment Company C in his early thirties, Hazelton suffered an extended illness. Hospitalized during the Battle of the Crater, which may have very well saved his life, he rejoined his unit to fight in the Third Battle of Petersburg, part of the Appomattox campaign. Petersburg fell on April 2, 1865. The 1870 and 1880 censuses list Hazelton as a farm laborer living with his wife and children. He died at age 54 in 1886 and was buried at Bryan’s Chapel Cemetery in Grasonville. Bryan’s Chapel recently replaced his headstone.

Another local USCT survivor of the war was Corporal Benjamin Frazier, who was 24 when he joined the army. Previously, Frazier was reported in the census as a servant of William and Margaret Eareckson of Kent Island. After the war, in 1870, he is identified as a laborer on the William and Margaret Eareckson farm with several other people. Similarly, a Philip Frazier, another soldier from the 19th Regiment, is listed in earlier censuses as part of the Cockey household. After the war, he is again listed with the Cockeys, then as a servant.

Isaiah Turner is identified as a Queen Anne’s County farmer in his enlistment document. Like Benjamin Brown, he was assigned to recruiting service in early 1864. But Private Turner survived. He endured the Battle of the Crater and two years in Brownsville after the war. Within twenty years of being mustered out, Turner owned property in Cambridge, where he farmed. His family, which included his wife Annie and two sons, William and Theodore Tecumsah, later lived on Cedar Street. In 1939, Annie Turner applied for a headstone to the War Department for her husband’s unmarked grave at Bethel Cemetery. He had died ten years earlier at the age of 85. Their son Theodore Tecumsah died in 1990 at age 90, and is also buried at Bethel Cemetery.

On April 18th [1864], the men of the 19th Regiment marched in a dress parade through downtown Baltimore and then boarded boats that took them to Annapolis. From Annapolis, the regiment marched to Washington D.C., where it camped near Georgetown for a couple of days. When orders were received to set out for Virginia, the regiment marched from Georgetown, past the White House, and then past the Willard Hotel on Pennsylvania Avenue where President Lincoln stood reviewing them. The regiment continued across the Long Bridge over the Potomac River and into Virgina where it joined up with General Grant’s Army of the Potomac. – Robert Summers, Maryland’s Black Civil War Soldiers, 19th Regiment US Colored Troops

These are just a few of the more than 200,000 USCT soldiers who served with distinction in the face of unthinkable risk—and all with stories to be told. While the Civil War placed all soldiers in horrific, unimaginable, traumatizing, and, for hundreds of thousands, deadly circumstances, the USCT also encountered unfair treatment in the army and much harsher treatment and grim threats from the enemy. For one, in 1863, the Confederate Congress threatened to enslave captured USCT soldiers or try them for insurrection, punishable by execution. And until June of 1864, USCT soldiers—some regiments which had been organized for longer than a year–were not paid equally and did not receive the same rations or supplies as white troops. For more than a century after the war, their valor and sacrifices generally went unrecognized.

This is something that has been changing. Locally, the Queen Anne’s County Veterans Committee is working toward establishing a statue honoring the county’s United States Colored Troops. For more information on this project, contact John Wright at Johncwright15@gmail.com or call 410-443-7686.

Also, pay a visit to the Kennard African American Cultural Center, located at 410 Little Kidwell Avenue in Centreville. The Center is open for free tours the first Saturday of each month 10:00 – 2:00 through October and by appointment at other times: 443-616-5341. They also offer group tours.

Lastly, mark your calendars November 29, 2025 through January 11, 2026, when the Kennard African American Cultural Center hosts the traveling Smithsonian exhibit Spark!: Places of Innovation, a Maryland Humanities Museums on Main Street project exploring the combination of places, people, and circumstances that sparks innovation in rural communities. Photographs, engaging interactives, objects, videos, and augmented reality will highlight local leaders, challenges, successes, and the future of local innovation.

Sources:

United States Colored Troops History:

https://afroamcivilwar.org/united-states-colored-troops-history/

National Archives:

https://www.archives.gov/education/lessons/blacks-civil-war

The Plight of the Black P.O.W. – New York Times https://archive.nytimes.com/opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/08/27/the-plight-of-the-black-p-o-w/

American Battlefield Trust, Calamity at the Crater

https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/calamity-crater

Virginia Humanities, Battle of the Crater:

https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/crater-battle-of-the/

“Men of color to arms! Now or never!”: https://www.loc.gov/resource/lprbscsm.scsm0556/?st=text

“United States Colored Troops Queen Anne’s County, Maryland,” https://qac.org/DocumentCenter/View/21044/P1, Chris Pupke

msa.maryland.gov

US Census Records

Military Enlistment Records

Maryland’s Black Civil War Soldiers, 19th Regiment US Colored Troops, Robert Summers

Back to Blog